-

Foreword Erwin Olaf

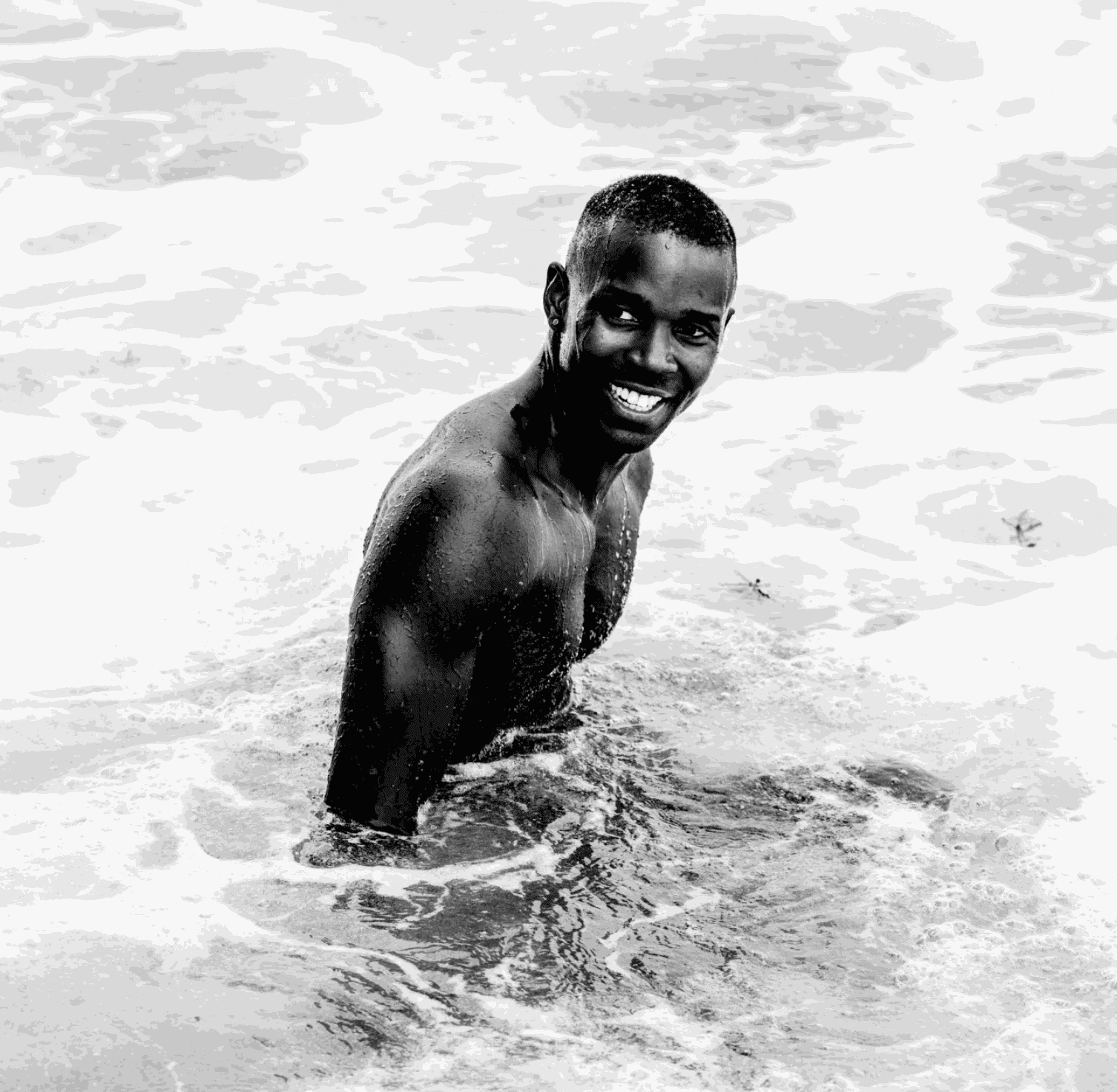

Download fileIt must have been about fifteen years ago when I received a letter in the mail, containing some photographs of a boy from a village not far from the Netherlands' largest harbor. The letter was signed by Ruben van Schalm, and from the pictures, Ruben himself watched his spectators with a mixture of embarrassment and ambition. I was intrigued by his fragile, pale appearance. Offering himself as model for me to work with, it certainly seemed worth the time to extend him an invitation for a photo shoot in my studio. Our photographic introduction resulted in some interesting photographs and ever since then, I have had a pleasure to work with Ruben on several occasions in photography and film, as well as the hedonistic parties that I have organized in Paradiso (Amsterdam's liberal temple of pop culture) with an emancipating goal, for often suppressed (sexuel) minorities in our society, As both an actor and model, Ruben always contributed to the process. In every project we have worked on together, he has given his full 100 percent. I remember the time when he asked, dressed as Commedia dell'Arte's miserable Pierrot, if I needed an extra 'kitsch' element. When I andswered affirmatively, it was matter of seconds before tears began to run down Ruben's face, his eyes expressing an immeasurable sadness. Just the detail I was looking for in this over-the-top, theatrical setting. Just like myself, Ruben has a profound love scenes of staged reality. What caught my eye during our time together was interested Ruben was in the technique behind the craft of photography. It came as no suprise to me when, after a few years, I learned he had taken up photography and had taught himself how to shoot and edit his photos in Photoshop. Initially, I was not overly impressed by his subject choice: beautiful, muscular men - are – obviously – pleasant to look at, but it quickly struck me as shallow and voyeuristic. I was not enthusiastic when Ruben told me he had the ambition to produce a book exclusively with 'sexy boys'. And I told him that. Soft porn is dull. But Ruben's ability to take constructive criticism to heart, improve from it, and further incorporate it into his work, impressed me. A few years after his first attempts, he sent me a series of photos which would later be published in the very book you are holding. I am pleasantly surprised to see how his style has developed. While the aesthetic of the nude male is still a leading subject of his work, Ruben nowadays combines it with power and poetry of nature. The artist has not only succeeded in capturing the beauty of man, but also the fragility of our surroundings as soon as we are outside of our urban bubble. And this has been captured and arranged in a beautiful rhythm for this publication. The Photographer paints a world in which he evokes a delicate balance between man and nature, illustrating how we much approach, respect and cherish the vulnerability of our surroundings. Ruben van Schalm stands on the shoulders of male nude photographers of prior generations, paying a tribute with this series of photos to the work of these men, the very source to which Wilhelm von Gloeden attributes his work. I am particularly curious and eagerly looking forward to seeing how Ruben's work will develop over the years to come.

Erwin Olaf, Amsterdam 2020

-

Essay

[...] And as I hear the wind

Rustling through these trees,

that infinite silence

I compare to this voice: and eternity

Occurs to me, and the dead seasons,

and the present one

Alive, with its sound. Thus, in this immensity

My thoughts drown:

And floundering in this sea is sweet to me.”

Giacomo Leopardi, The Infinite, 1819Marth von Loeben

Whether we believe in its existence or not, the concept of paradise has always excited the imagination of poets, theologists and philosophers. Usually taking the shape of an idyllic, otherworldly habitat on a higher plane unspoiled by earthly faults and stains, it has always been a place where souls could dwell unperturbed by pain, jealousy and calamities. Often, it has been portrayed with breathtaking beauty too, symbolizing what the different cultures assumed as the superlative expression of peace. The Elysium in Greek mythology, for example, was the final resting place of heroic souls; a set of islands that bore sweet fruits and was caressed by a gentle wind. Similarly the Valhalla — the Norse depiction of the afterlife — was a majestic hall in Asgard where those who fought with valour would feast for eternity alongside Odin. Heaven, as well, in Christian religion is the perfect residence of the Throne of God, whose holy light flows over the angels and all the good souls seated around him. Despite how all these representations may sound magnificent, though, none of them leaves any space to personal interpretation or to the desires of the individual.

At the core of the book by Ruben van Schalm, instead, paradise does not look like an untroubled environment but is rather a place overruled by the elements of nature, with at the centre its quintessential component: man. The journey towards finding and creating this very personal vision of paradise, though, has been many years in the making. It was a journey of introspection, going down a path laid with shaky pebbles, but nevertheless essential because driven by an innate will to create and to reveal a particular vision. Years of research, travels, and collaborations with like-minded individuals have shaped what we can see now in the pages of this book: an artistic force that found its calling in the portrayal of the relationship between man and nature.

The artistic force that has always pervaded Ruben van Schalm has taken many shapes over the years: it led him to move to Amsterdam to be at the centre of creativity in the Netherlands; it led him to experiment with acting, at first, and then to model for artists and photographers, which later brought him to the studio of Erwin Olaf. This talented and renowned Dutch photographer opened van Schalm’s eyes over the wonders of this versatile medium, and over how inventive it could become once it was mastered and focused properly. A world of unmatched beauty and possibilities was revealed, and the first contact with it was through a small analogue camera bought at a second-hand market. The suffocating condition that Amsterdam was still imposing over van Schalm, though, influenced him greatly in his first experiments with film, which were more an expression of escapism than a clear initial step in the development of his visual taste. Paradise was waiting, but the journey towards finding it still had to start.

The first contact with ‘Paradise’ was in the shape of a person, a lovely man named Guy who would later become van Schalm’s life companion. This treasured meeting acted as a springboard for van Schalm, pushing forward both his artistic development and his personal identity. By moving to Tel Aviv with Guy, van Schalm started expressing himself more freely and was rapidly inspired by the rough, untouched nature surrounding the city. Nature in Israel felt overwhelming and absolute, like nothing that the Netherlands could offer: it was a landscape that challenged human presence, that was not easy to reach, discover or explore. But the wonders and beauty found in it were unparalleled. The journey towards visual maturity had begun, and the transition period that would soon follow took the shape of a black Icarus that had fallen in the desert and was haunting his surroundings: he had to plummet down in order for the next muses to soar.

Once the lid to the vase of creativity was off, the process towards finding ‘Paradise’ developed very easily, almost organically: the discovery of new natural landscapes while travelling, the different challenges to the shooting sessions and new enthusiastic people to be featured in the projects all came together in an unrestricted atmosphere of communion with the elements. This freedom was also exalted in the kinship between van Schalm and his muses: the models were not hired beforehand, sometimes they wouldn’t even be professionals. They were found on location and asked to become part of an art project out of personal interest and excitement in trying something new. This convergence would create an intimate relationship that would later greatly improve the production process and the quality of the images as well. The inclusion of these vigorous models mirrored and highlighted the beauty of the scenery: they were an expression of what the Greek philosophers referred to as kalokagathia, an ideal of physical and moral perfection reflected in the prowess of the body. Two exemplary statues following this concept (and that greatly resemble the muses of van Schalm) are the Riace bronzes,1 two warriors whose figures were immortalized in the impossible perfection of the Classical statuary canons of Polykleitos. The sites framing the individuals were also chosen carefully, not only for the unique natural features they offered but also because of their secluded quality. The advantage of these locations was to be out of sight, so that the private atmosphere among the team would allow them to act freely during the shooting, without having to worry about any external interruption. Thus, nature, the artist and the muses came together to produce something that was more than the sum of its parts: it was an expression of Sublime.

The concept of Sublime used to be very popular amongst philosophers, writers and artists at the end of the 18th century, and it celebrated the inclusion of greater values and emotions in the aesthetics of art. These ideals were mainly visualized as monumental natural landscapes, contemplated by various individuals featured in the layout. The sentiment of sublime, though, was not found in the faithful and realistic depiction of the details in the landscapes, but in the ability of the painter to convey the overwhelming force of nature through the use of colours and composition, especially through the careful choice of the scenes represented. Therefore, instead of having an idyllic, perfect forest as you might find it in Botticelli’s Spring,2 the viewer would encounter the mysterious stretch of clouds amongst the sharp rocks of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.3 The role of characters in Neoclassical paintings was also very important, as it is in the photographic production of van Schalm: not only do they focus the viewer’s attention in the composition, but they offer an empathic hook to become directly immersed in the natural scene. The viewer does not only look at them but looks at the scene through their eyes.

In this book, the reader is presented with a vision of paradise that encompasses all emotions, from the softest to the roughest. The sheer power of the elements is shown as it can be found in nature: overwhelming, changeable and clashing with human presence. The models are both overpowered by nature and at harmony with it, depending on the state they find themselves in. Nothing is polished: both the muses and the landscape are left as pristine as they are found. This wide range of emotions and visual examples is an invitation to build a personal paradise, one that is untethered to the generic and passive representations imposed on the public imagination by centuries of intellectual heritage. The variety of van Schalm’s photographic production resembles the variety found in nature and in the hearts of people, and the reader is encouraged to shape their own personal paradise by having their imagination thrilled by the visual qualities of the photographs.

-

Myron (attributed), Statue A (450 B.C.), bronze cast, 198 cm, Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia, Reggio Calabria, Italy; Alkamenes (attributed), Statue B (450 B.C.), bronze cast, 197 cm, Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia, ReggioCalabria, Italy.

-

Sandro Botticelli, Spring (1478), tempera on canvas, 203Å~314 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze, Italy.

-

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1817), oil on canvas, 98Å~74 cm, Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany.

-